Ask The Doc

How can I train and play at the highest frequency but have the lowest chance of injury?

This has always been a concern. Players will report, “I need to play enough matches and do enough conditioning to be at my best ability level, but I am concerned that I will ‘overdo’ it.” OR, “I’ve seen that players may have a high level of conditioning then play and do well, while others who try that level get injured.” In many cases, the problem can best be understood by examining the “load” a player experiences in tennis. “Load” is the total demand placed on the player as the result of all the activities required in playing. This article will only address the physical load, although the mental load also has implications and will be discussed in another article.

Load is a combination of the strokes hit, distance run, intensity of play, the content and amount of conditioning, and rest/recovery from a tennis session, and is usually called the training load. For many years it was thought that the total amount of the training load should be kept below a certain level, although it was difficult to accurately establish that exact level. There were many problems with this approach – people whose training load was below that level could get injured and some whose training load was above that level did well. Most current evidence shows that most overload injuries are not caused by training or competition per se, but by inappropriate training or competition. It appears that the change in training, going abruptly from a certain level of load to a different level of load, is more important than the actual amount. Anyone who has played tennis twice a week and then went to a tennis camp and played twice a day or to a tournament and played 2 matches a day knows about the effects of an acute change in training load.

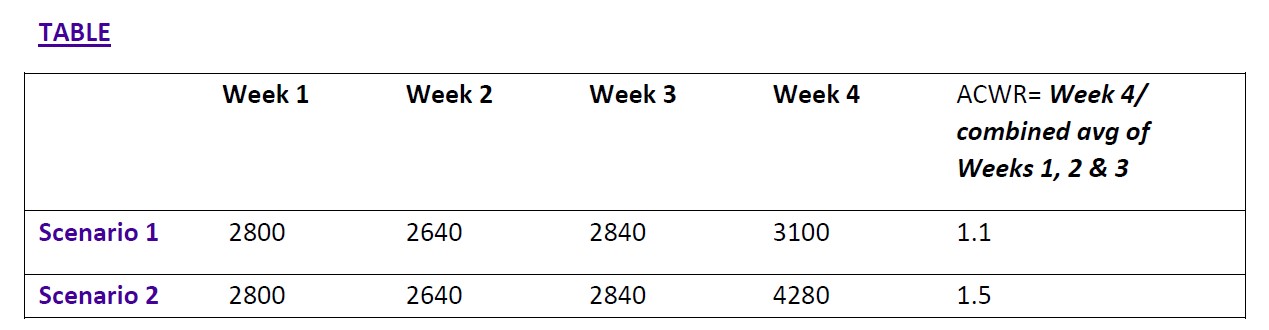

For most tennis players, the 2 most important variables in creating the training load are the number of strokes hit and the time on court. Keeping a log of the time on court and an estimation of the total number of balls hit will help in knowing the load. This measurement is determined for a week at a time. If a player is on the court for 4 hours, and hits 700 balls, then the load would be 2800 for that week (4 x 700= 2800). To identify significant change in load, the acute/chronic workload ratio (ACWR) can be calculated by relating one week’s load to the average load from the previous 3 weeks. If the ratio is greater than 1.5, studies have shown that the risk of injury is higher by 43%. The effect is the same for players who play rather infrequently and those who play regularly. (See TABLE below.)

For Scenario 1, the load is within the body’s usual capabilities (under 1.5). For Scenario 2, the injury risk is much higher (1.5 or above).

The ACWR can be calculated on a rolling basis, always comparing the latest load to the average of the most recent loads. That way you have a current estimate of your workload.

Large changes in load may overwhelm the body’s capabilities to withstand the loads. A way to lower the risk of overload is to monitor weekly loads and try to maintain a consistent amount, or by gradually increasing the load by less than 10% (ratio 1.1) if you are trying to play more or prepare for a tournament.

Additional strategies to help avoid overload include optimum conditioning as discussed in previous “Ask the Doc” articles, and by emphasizing recovery, both rest and sleep.